Education-Based

Evaluations for

Autism Spectrum Disorder

September 9, 2015 www.michigan.gov/autism

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. 3

Purpose ................................................................................................................................. 3

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4

Michigan Administrative Rules for Special Education (MARSE) ASD Eligibility Criteria ............. 5

MARSE Eligibility Criteria.......................................................................................................................... 5

Qualitative Impairments in Reciprocal Social Interactions ................................................................... 6

Qualitative Impairments in Communication ......................................................................................... 8

Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Behaviors ............................................................................. 10

Unusual or Inconsistent Response to Sensory Stimuli ......................................................................... 12

Age ...................................................................................................................................................... 12

Adverse Impact....................................................................................................................................... 12

Academic ............................................................................................................................................. 13

Behavioral ........................................................................................................................................... 13

Social ................................................................................................................................................... 13

Need for Special Education Programs and/or Related Services ............................................................. 14

Education-based Evaluation for ASD .................................................................................... 14

Review of Existing Evaluation Data (REED) ............................................................................................ 16

Completion of Evaluation Components .................................................................................................. 16

Results Review Meeting ......................................................................................................................... 21

Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team Report ............................................................................................. 22

Individualized Education Program ......................................................................................................... 23

Differential Eligibility Decision-Making ................................................................................ 23

Considerations for Evaluation of Young Children .................................................................. 25

Appendices ......................................................................................................................... 28

References .......................................................................................................................... 44

The Michigan Autism Council 2 www.michigan.gov/autism

Acknowledgments

Writing/Drafting Team

Autism Council Education Subcommittee Evaluation Workgroup

Dorie France, Rob Dietzel, Joanne Winkelman, Stephanie Dyer, and Kelly Dunlap

Lead Editors

Stephanie Dyer and Kelly Dunlap

Reviewers

Deb Koepke, Pamela Lemerand, Valerie Mierzwa, Leigh McFarland, and Lindsey Harr-Smith

Significant Contributions

Clinton County Regional Educational Service Agency (RESA) Evaluation Process, Charlevoix–

Emmet Intermediate School District (ISD) Autism Spectrum Disorder Eligibility Guidelines,

and Centralized Evaluation Team Process (Dave Schoemer and Maureen Ziegler)

Purpose

The Michigan Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) State Plan recommends that education-

based multidisciplinary evaluation teams have access to information and training in ASD

eligibility determination to improve the consistency of practices. The purpose of this

document is to provide guidance to schools to develop evaluation processes to ensure

accurate eligibility decisions, improve cross-agency collaboration to reduce duplication,

ensure a seamless process for families, and provide relevant information to inform the

Individualized Education Program (IEP). In some instances, this document addresses

considerations of evaluation components that exceed requirements of federal law

or Michigan Administrative Rules for Special Education (MARSE).

The Michigan Autism Council 3 www.michigan.gov/autism

Introduction

The purpose of an education-based evaluation is to determine a student’s eligibility for

special education programs or services under the MARSE criteria, not to provide a clinical

diagnosis. However, according to the Michigan ASD State Plan survey (2012), there is often

confusion between a clinical diagnosis of ASD and ASD special education eligibility criteria.

The confusion is further exacerbated when a child receives a clinical diagnosis of ASD but

then does not meet the education-based eligibility criteria under ASD. As such, it is

important to outline the differences in process and purpose of evaluations between the two

to enhance understanding across school personnel, clinical staff, and families. Below is a

brief comparison of the various components of evaluation across the school and clinical

models:

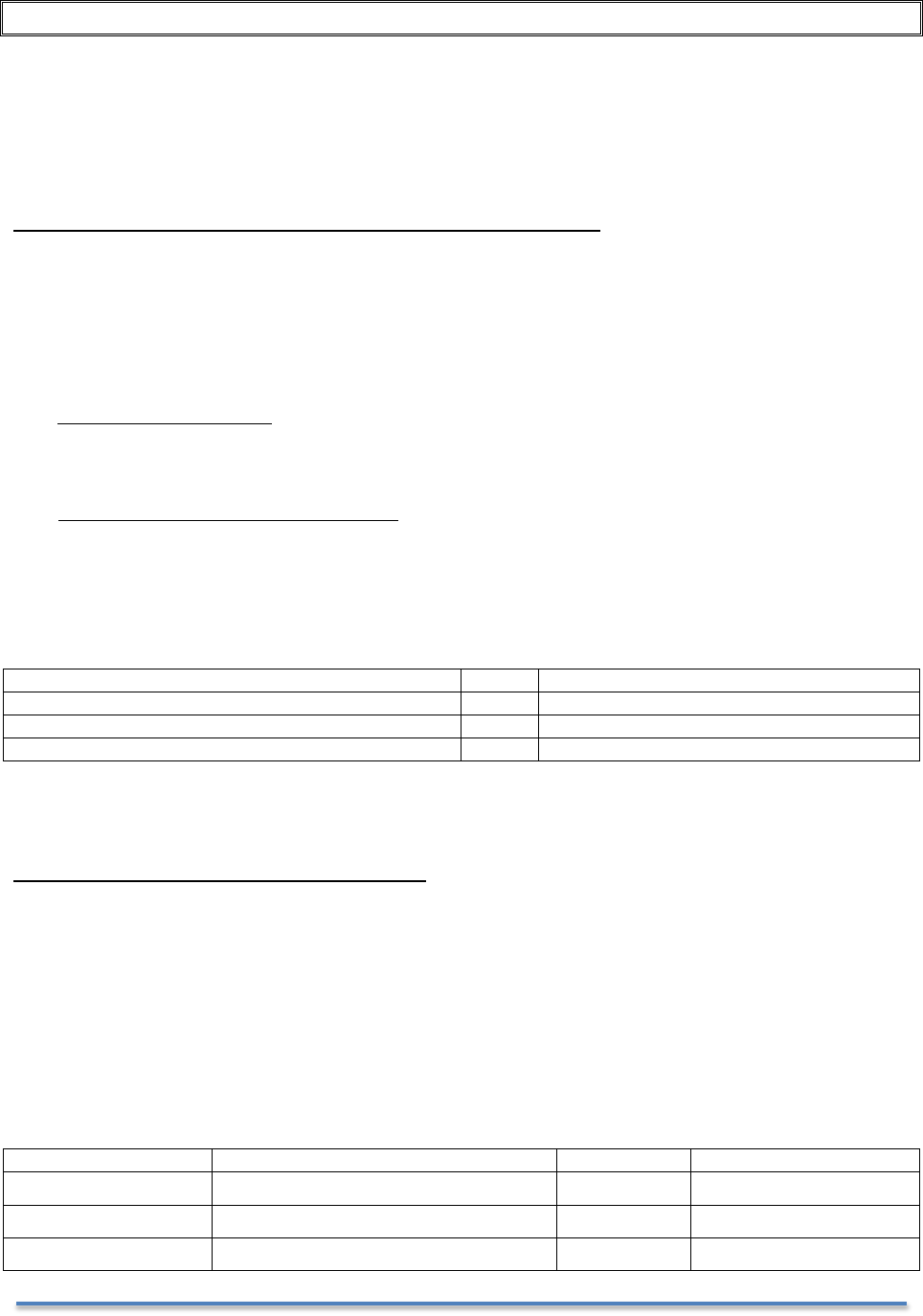

Education-Based Eligibility

Clinical/Medical Diagnosis

Purpose/

Function

• Determine special education

eligibility or ineligibility

• Determine educational impact

• Determine need for specially

designed instruction

• Inform IEP and special

education services

• Make Clinical/Medical/

Behavioral Health Diagnosis

• Determine insurance or Medicaid

Autism benefit eligibility

• Access non-educational agency

services

• Dictate medical/clinical treatment

Criteria/Tools

to Make

Determination

• MARSE ASD criteria

• Use of tools individually

determined based on what

questions need to be

answered

• Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

for Mental Disorders Fifth Edition

(DSM-5)

• Clinical diagnostic assessment

tools (e.g. Autism Diagnostic

Observation Schedule (ADOS))

• For additional information, see

Medical Services Administration

(MSA) Bulletin 13-09

Team

Members

• Multidisciplinary team

including a psychologist/

psychiatrist, authorized

provider of speech and

language services, and school

social worker are required

• Practitioners can make

independent diagnostic decisions

Plan for

Evaluation*

• Review Existing Evaluation

Data (REED)

• No evaluation plan requirement

Observations**

• Multiple observations in

varied environments over

time

• Generally includes observations in

an office or clinic setting

*Not required for initial evaluations, but recommended

**Not required, but considered a necessary component

Because the process and purpose for evaluations are different, a clinical diagnosis of ASD is

not required or sufficient for the determination of special education eligibility. If clinical

diagnostic information is available, it must be considered in the evaluation process, but the

The Michigan Autism Council 4 www.michigan.gov/autism

final determination of eligibility may still require additional education-based assessments or

observations.

Further, given these differences in tools and processes, it is not uncommon for

disagreements in ASD eligibility and diagnosis to occur. As such, it is important for

education-based multidisciplinary evaluation teams and clinical evaluators to work

collaboratively to assist families in understanding these differences and the reasons the

differences exist. Information on effective collaboration can be found in the Michigan Autism

Council’s Collaboration Matrix (2014).

In recent years, progress has been made in both the clinical and educational fields in the

assessment and identification of ASD. This document outlines the core components of

eligibility determination for ASD.

Michigan Administrative Rules for Special

Education (MARSE) ASD Eligibility Criteria

As it is with all eligibility areas, special education eligibility for ASD is a three-pronged

process:

1. The student must meet the MARSE eligibility criteria for ASD,

2. The ASD must adversely affect the student’s educational performance in

academic, behavioral, or social domains, and

3. The impact must require and necessitate special education programs and/or

services.

A multidisciplinary evaluation team is required to provide evidence in all three areas to

determine a student eligible for special education programs and/or services. Below is

information to assist the multidisciplinary evaluation team in gathering relevant data to

address all three required areas of eligibility.

MARSE Eligibility Criteria

To meet the MARSE eligibility criteria for ASD, a student must demonstrate characteristics in

all three of the following domains:

1. Qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interactions,

2. Qualitative impairments in communication, and

3. A restricted range of interests or repetitive behavior.

Two additional factors may be considered in determining eligibility under the ASD criteria:

4. Unusual or inconsistent response to stimuli

5. Age

The Michigan Autism Council 5 www.michigan.gov/autism

The complete the MARSE eligibility criteria (R 340.1715) are found in Appendix A. However,

a review of the three domains with example behavioral characteristics is provided below:

Qualitative Impairments in Reciprocal Social Interactions

A qualitative impairment is defined as atypical or considerably different from other students

the same age. According to MARSE, a qualitative impairment in reciprocal social interactions

would include at least two of the following four characteristics:

1. Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors, such as eye-to-

eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures, to regulate social

interaction.

Marked impairment in this area means substantial and sustained difficulty using

nonverbal behaviors to augment communication for the purposes of the social partner.

This criterion is not intended to define the presence or absence of nonverbal behavior

but rather the use of nonverbal behavior to regulate social communication, particularly

where words fail.

Marked impairment also implies that the difficulties are clearly evident and observed

across multiple environments and people over time. Evidence of marked impairment in

nonverbal behaviors may include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Differences in eye-to-eye gaze (e.g. seems to look “through” a person, limited or no

eye contact or eye gaze to initiate, sustain, or guide social interaction, has fleeting or

inconsistent eye contact)

• Differences in facial expression (e.g. lacks emotion or appropriate facial affect for the

social situation, lacks accurate facial expression to reflect internal feelings, facial

expressions seem rehearsed or mechanical, limited or no use of facial expression to

guide communication)

• Differences in body posture (e.g. difficulty maintaining appropriate body space,

awkward/stiff response or movement, gait challenges)

• Differences in spontaneous use of gestures (e.g. lacks understanding of the use of

nonverbal cues (e.g. pointing, head nod, waving), does not respond to

communication partner signals to start or end a conversation)

2. Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level.

Students may fail to develop appropriate peer relationships for a variety of reasons. For

students with ASD, failure to develop reciprocal relationships with peers results from

deficits in social reciprocity (i.e. the give and take in social interaction) and the inability

to understand the perspectives of others.

In addition, the quality of peer relationships must be made in comparison to peers at the

same age and developmental level. Evidence of failure to develop reciprocal peer

relationships may include, but is not limited to, the following:

The Michigan Autism Council 6 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Lack of understanding of age-appropriate humor and jokes

• Disruption of ongoing activities when entering play or social circles; may insist on

controlling the play when engaging with others

• Lack of initiation or sustained interactions with others

• Preference to play alone

• Continuous failure in trying to understand social nuances and follow social rules

• Desire for friendships but has multiple failed attempts

• Misinterpretation of social cues or communication intent of others

• Tolerance of peers but no spontaneous engagement in conversation or activity

• Confusion with the telling of lies

• Policing peers (e.g. reporting rule infractions on the playground)

3. Marked impairment in spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or

achievements with other people (e.g. a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing

out objects of interest).

Marked impairment in this area means substantial lack of spontaneous (i.e. without

prompting) sharing and showing, often referred to as joint attention. According to Oates

& Grayson (2004), joint attention is defined as the shared focus or experience of two or

more individuals on an object or activity. This typically begins to develop around two

months of age with dyadic (i.e. two persons) exchanges using looks, noises, and mouth

movements. Lack of sharing with others also results from deficits in understanding the

perspectives of others.

Marked impairment in this area must be clearly evident across multiple people and

environments over time. Evidence of impairment in spontaneous seeking to share may

include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Deficits in the use of pointing to orient another to an object or event

• Limited number of attempts to share achievements or items of interest with others

as compared to peers

• Bringing objects or items to others for the purposes of getting needs met, but not for

a shared experience

• Lack of response to others sharing enjoyment, interests, or achievements (e.g.

shifting conversations to one’s own interest rather than responding to the interests

of others)

4. Marked impairment in the areas of social or emotional reciprocity.

Reciprocity is defined as the mutual give and take of social interactions. Marked

impairment in this area implies significant difficulty recognizing and responding to the

needs, intentions, perspectives, and feelings of others across multiple environments and

people over time. Evidence of impairment in social or emotional reciprocity may include,

but is not limited to, the following:

• Limited to no use of social smiling; rarely offers spontaneous social smiles

• Lack of interest in the ideas of others

The Michigan Autism Council 7 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Aloofness and indifference toward others

• Seemingly rude statements to others without filter or negative intent (e.g. telling

someone to stop eating chips because they are fat, as if they are doing that person a

favor)

• Difficulty explaining their own behaviors in context of impact on others

• Difficulty predicting how others feel or think

• Problems inferring the intentions or feelings of others

• Failure to understand how their behavior impacts how others think or feel

• Problems with social conventions (e.g. turn-taking, politeness, and social space)

• Lack of appropriate response to someone else’s pain or distress (e.g. laughing when

others are upset)

• Creating arbitrary social rules to make sense of ambiguous social norms (e.g. “All

people fall into one of three categories: jocks, friends, or people who make bad

decisions.”)

Qualitative Impairments in Communication

A qualitative impairment is defined as atypical development or considerable differences as

compared to other students the same age. According to MARSE, qualitative impairments in

communication include at least one of the following:

1. Delay in or total lack of the development of spoken language not accompanied

by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication

such as gesture or mime.

Typical development of language includes babbling by 12 months, single word use by 16

months, and two-word phrases by 24 months of age. Some children fail to develop

language yet compensate by using alternative communication modes such as gestures,

facial expressions, and other nonverbal behaviors.

Some children with ASD, however, do not seem to recognize that words have a

communicative intent. As such, they fail to compensate for their lack of language

development, although they may ensure their needs get met (e.g. using an adult as a

tool to get a snack or toy or shoving someone to get them out of the way).

In some instances, children with ASD may begin to develop spoken language and then

lose the language they have acquired. Evidence of delay in or lack of the development of

spoken language not accompanied by attempts to compensate may include, but is not

limited to, the following:

• Pulling an adult to a particular area to get a snack or toy

• Standing or screaming near the refrigerator in the absence of an adult

• Use of words not directed at others (e.g. gibberish, mumbling)

• Challenging behavior in lieu of alternate communication (e.g. hitting, biting, pushing,

screaming)

The Michigan Autism Council 8 www.michigan.gov/autism

2. Marked impairment in pragmatics or in the ability to initiate, sustain, or engage

in reciprocal conversation with others.

“Pragmatics” is a term used to explain the give and take of social language. Deficits in

pragmatics for students with ASD result from deficits in understanding the perspectives

of others and lack of social reciprocity.

Marked impairment implies that difficulty with pragmatics is clearly evident in multiple

environments and people across time. Evidence of marked impairment in pragmatics

may include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Difficulty with the social aspects of language (e.g. understanding non-literal language

used in conversation)

• Issues with prosody (e.g. flat and emotionless or high and pitchy with atypical

rhythm or rate)

• Difficulty changing language according to the needs of the listener (e.g. not giving

background information to an unfamiliar listener or not speaking differently in a

classroom than on a playground)

• Difficulty initiating, sustaining, or ending conversations with others

• Difficulty using repair strategies when communication breaks down

• Difficulty following the rules of conversations and storytelling (e.g. taking turns in

conversation, staying on topic, rephrasing when misunderstood, proximity, use of

eye contact)

• Talking for extended periods of time about a subject of the student’s liking,

regardless of the listener’s interest

• Talking at someone in a monologue rather than conversing

• Interpreting what others say according to the most basic or literal meaning

3. Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language.

Students with ASD may exhibit stereotypical (i.e. use of nonsense words or phrases or

verbal fascinations) and repetitive or idiosyncratic language (i.e. contextually irrelevant

or not understandable to the listener due to a private meaning). Evidence of

stereotyped, repetitive, or idiosyncratic language may include, but is not limited to, the

following:

• Repeating words or phrases over and over

• Repeating what others say (echolalia) either immediately after the person said it or

at some time in the future

• Repeating television or movie lines, song lyrics, or other media that are out of

context and add no meaning to the conversation

• Use of words with a private meaning that only makes sense to those who are familiar

with the situation where the phrase originated (e.g. every time the student enters

the room he states, “That’s right on the money!”)

• Talking about a specific topic incessantly and out of context

• Overly formal use of words or expressions in conversation

The Michigan Autism Council 9 www.michigan.gov/autism

4. Lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play

appropriate to developmental level.

Spontaneous make-believe play is a precursor to the use of symbols and corresponds

with language development. Social imitative play is also thought to be an early sign of

social reciprocity. Evidence of the lack of these behaviors may include, but is not limited

to, the following:

• Lack of spontaneous pretend play with toys (e.g. using objects only as they are

intended)

• Little elaboration on learned play schemes

• Lining up toys like cars or trains, stuffed animals, or action figures

• Focusing on only a part of the toy rather than actually playing with it (e.g. wheels on

a toy car or train, the string of a pull toy) or focusing on the movement of the toy

rather than the purpose of the toy; stacking blocks but not building anything

• Lack of finger play (e.g. “Itsy Bitsy Spider”) imitation without specific teaching and

prompts

• Limited play repertoires compared to peers (e.g. only plays with one specific toy or

item)

• Lack of advancement of play repertoires over time (e.g. still playing with Thomas the

Tank Engine while peers have moved on to LEGO® or board games)

• Rather than playing, directing peers to their assigned role in play

• Engages in construction play (e.g. puzzles, building blocks, assembling Transformers,

LEGO® bricks, setting up elaborate train track layouts) at the exclusion of flexible

representational play

Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Behaviors

Students with ASD engage in restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors that are

extreme and often interfere with other more appropriate behaviors or learning. Because

students with ASD are driven to engage in these behaviors, they are difficult to stop or

control. Further, disrupting the behaviors often causes significant distress for the student.

According to MARSE, restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors must include at least

one of the following:

1. Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted

patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus.

Students with ASD can display intense interests and preoccupations that are intrusive,

reoccur frequently, and interfere with participation in daily activities. Limited access,

interruption, or removal of the activity or interest often causes significant distress.

Evidence of preoccupations and interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus may

include, but is not limited to, the following:

The Michigan Autism Council 10 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Talking about a particular topic (e.g. The Weather Channel) incessantly without

regard to the conversational partner

• “Playing” with the same toy over and over again and in the same way each time

• Incessantly seeking access to or talking about seemingly typical interests for age

such as video games (e.g. Minecraft), topic areas (e.g. anime), and characters (e.g.

SpongeBob or The Simpsons) but to the exclusion of most other topic areas or

activities

• Using a specific video game, television show, or movie as the lens through which

experiences or the world are viewed

• Excessively seeking access to or talking about atypical interests such as historical

events (e.g. Siege of Malta), specific appliances (e.g. coffee machine or fan), or

unusual types of animals (e.g. white Siberian tiger)

• Excessively seeking access to or talking about interests atypical for age (e.g. the

digestive system at age 4 or Thomas the Tank Engine at age 15)

2. Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals.

Students with ASD seek predictability in their environments and thus may create and

follow nonfunctional routines or rituals or have extreme distress when their routines are

altered. Evidence of inflexible adherence to nonfunctional routines or rituals may include,

but is not limited to, the following:

• Wearing a specific clothing item for a specific day or activity

• Rigid adherence to specific sequences in routines (e.g. eating food in a specific order,

completing worksheets from the bottom or right side only)

• Excessive and time consuming routines (e.g. bathroom, dressing)

• Distress when daily routines and schedules are altered

• Alphabetizing videos by the last name of the producer

• Having unusual self-imposed rules (e.g. must pass three red cars before entering

school)

• Insistence that others follow rules, including rules made up by the student

3. Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g. hand or finger flapping or

twisting, or complex whole-body movements).

Some students with ASD engage in repetitive motor mannerisms, often called self-

stimulatory behaviors. Self-stimulatory behaviors occur in other disabilities as well, so it

is crucial for multidisciplinary evaluation teams to consider this item in context to the

other criteria. Evidence of stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerism may include, but

is not limited to, the following:

• Preoccupation with fingers, spinning, and twirling objects or self

• Pacing in a particular manner or routine

• Smelling, chewing, or rubbing objects in a particular manner

• Rocking or lunging

• Persistent grinding of teeth

• Repeated visual inspection of objects

The Michigan Autism Council 11 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Self-injurious behaviors including head-banging, hand biting, and excessive self-

rubbing and scratching

4. Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects.

Students with ASD can become preoccupied with parts, objects, or processes. The

fixation may appear to be more focused on how an object, including toys, actually works

instead of the function that it serves. Evidence of persistent (i.e. occurring over a

prolonged period of time) preoccupation with parts of objects may include, but is not

limited to, the following:

• A fascination with a specific part of the dishwasher or vacuum cleaner

• Spinning the wheels of a car

• Watching several seconds of a movie or cartoon over and over again, without

watching the complete movie

• Completing complex puzzles with more interest in putting the pieces together than

the puzzle picture as whole

Unusual or Inconsistent Response to Sensory Stimuli

Students with ASD may seek or avoid certain sensory stimuli to a degree that it interferes

with daily activities. Specific sensory areas can include sight, touch, hearing, smell, taste,

and movement.

According to MARSE, determination of ASD may include unusual or inconsistent responses

to sensory stimuli, but to be eligible under ASD, the student must also meet the other three

domains of eligibility. Sensory challenges alone are not sufficient to identify the student as

ASD because sensory issues can be found in a number of other eligibility areas. Conversely,

the absence of sensory challenges does not exclude a student from meeting ASD eligibility

criteria. As such, the evaluation team should analyze the child’s response to sensory stimuli

as it impacts the three domains of ASD eligibility (i.e. reciprocal social interaction,

communication, and restrictive and repetitive behaviors).

Age

According to MARSE, ASD typically manifests before 36 months of age. A child who first

manifests the characteristics after age three may also meet criteria, although generally the

child should have indicators of developmental differences by 36 months of age.

Adverse Impact

Determine if the ASD has an Adverse Educational Impact

According to MARSE, in order to be eligible for special education programs and services, a

student’s disability (i.e. ASD) must adversely affect educational performance in academic,

behavioral, or social domains. As such, a student may meet the eligibility criteria for ASD

but not be eligible for special education because access and progress in the general

education curriculum or environment is not affected by the ASD.

The Michigan Autism Council 12 www.michigan.gov/autism

Traditionally, multidisciplinary evaluation team members used the impact on the academic

domain alone as a determining factor in educational impact; however, for eligibility under

ASD, a student can have impact in any one of these three domains. A description of each

domain and the behaviors associated with them is provided below:

Academic

Determining adverse educational impact in the academic domain requires a review of the

student’s ability to meaningfully participate and progress in the general curriculum.

Evidence of academic impact may include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Delayed academic skill acquisition (e.g. reading, math, writing)

• Limited participation and engagement in instruction

• Lack of initiation and completion of school and home work

• Low grades and scores on academic assessments

Behavioral

Determining adverse educational impact in the behavioral domain requires a review of any

behavioral challenges that interfere with the student’s ability to meaningfully participate and

progress in the general curriculum or integrated environments (e.g. classroom, hallways,

lunch room, bus). Evidence of behavioral impact may include, but is not limited to, the

following:

• Aggression (e.g. hitting, kicking, spitting)

• Temper tantrums (e.g. dropping to the floor, crying, screaming)

• Disruptions (e.g. yelling, loud insistence that others are wrong and the student is right,

noises such as barking and humming)

• Non-compliance (e.g. not completing work or assessments, not following directions)

• Self-stimulatory behaviors (e.g. rocking, repetitive language, flapping)

• Eloping (e.g. running away, leaving the environment, hiding)

Social

Determining adverse educational impact in the social domain requires a review of the

student’s social interaction skills, relationship development, and engagement in the social

environment. Evidence of social impact may include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Difficulty making and keeping friends

• Challenges with reciprocal social interaction

• Difficultly understanding the perspectives of others (e.g. asks impolite questions; insists

on getting needs met even if someone nearby is upset; insists on always being first in

line; insists on winning all games)

• Obsession with peers following the rules (e.g. tattling on every infraction)

• Difficulty working cooperatively in groups

• Lack of independence in daily routines

• Transition challenges

The Michigan Autism Council 13 www.michigan.gov/autism

Need for Special Education Programs

and/or Related Services

According to the regulations for implementing the

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), to

be eligible for special education services, the

educational impact of the student’s ASD must

necessitate special education programs and/or related

services (§300.306). Special education is defined in

§300.39 as specially designed instruction.

The regulation further defines specially designed

instruction as “adapting, as appropriate to the needs

of an eligible child… to address the unique needs of

the child that result from the child’s disability.”

For example, specialized instruction must be needed for the student to make progress in

school and benefit from general education instruction to be eligible for services; having the

disability alone does not guarantee eligibility. Effectiveness of previously implemented

interventions is one way to determine the need for specialized instruction.

Education-based Evaluation for ASD

An education-based evaluation for ASD and recommendation of eligibility should not be

made based on any single evaluation component (e.g. interview, observation, test scores),

but rather each piece should be viewed as data to complete the evaluation picture.

Once the data is collected, the multidisciplinary evaluation team, using the preponderance

of evidence, makes a recommendation about whether or not the student meets the three-

pronged eligibility criteria:

1. The student meets the MARSE eligibility criteria for ASD,

2. The ASD adversely affects the student’s educational performance in academic,

behavioral, or social domains, and

3. The impact requires and necessitates special education services.

In addition to meeting the three-pronged eligibility requirements, the multidisciplinary

evaluation team must also gather information to assist in developing the Individualized

Education Program (IEP). This could include information such as:

• Communication needs of the student, including assistive technology

• The student’s social needs, including peer to peer support

• The student’s behavioral needs, including the need for a functional behavioral

assessment, positive behavioral support plan, and/or emergency crisis plan

“There is no single behavior

that is always typical of

autism and no behavior that

would automatically exclude

an individual child from a

diagnosis of autism.”

—National Research Council, 2001

The Michigan Autism Council 14 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Academic needs of the student, including accommodations and differentiation

Further, the multidisciplinary evaluation team is required to consider all suspected

disabilities. As such, a full and individual evaluation should include information to assist in

making differential eligibility recommendations (e.g. cognitive impairment, emotional

impairment, learning disability) if these disabilities are suspected.

Before beginning the eligibility determination process, a multidisciplinary evaluation team

(MET) must be established. Minimally, MARSE requires that the MET be comprised of a

psychologist/psychiatrist, school social worker, and authorized provider of speech and

language services. Although additional multidisciplinary evaluation team members can be

utilized, they are not required.

Additionally, some districts have opted to use a systematic team configuration model to

build capacity among staff and address specific challenges that may arise in some

evaluations. A description of the optional team configurations can be found in Appendix B.

The multidisciplinary evaluation team should function as a coordinated unit throughout the

evaluation process, regardless of the configuration or model used.

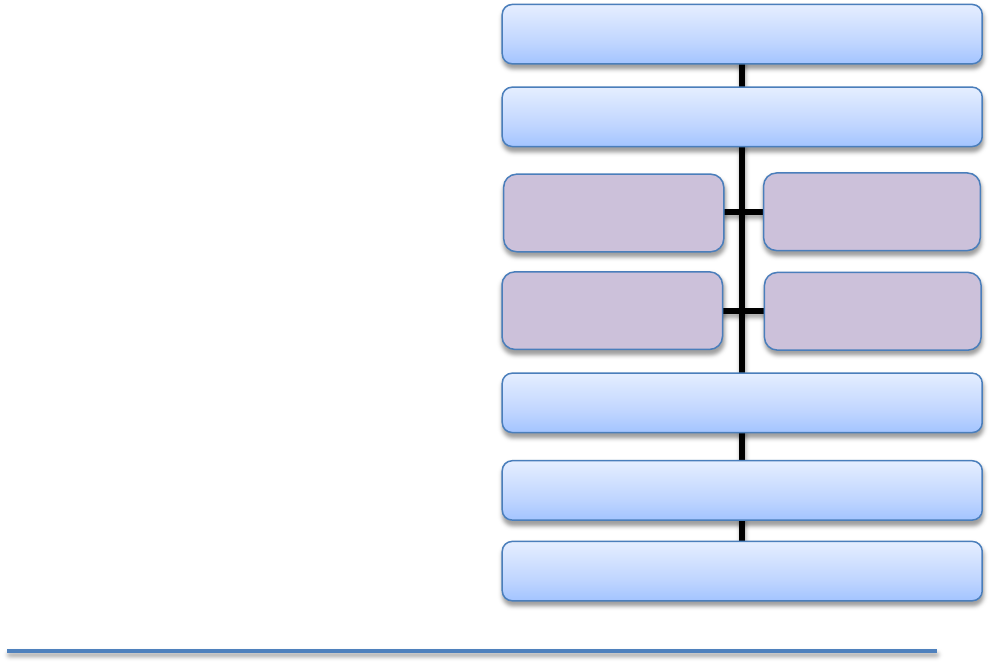

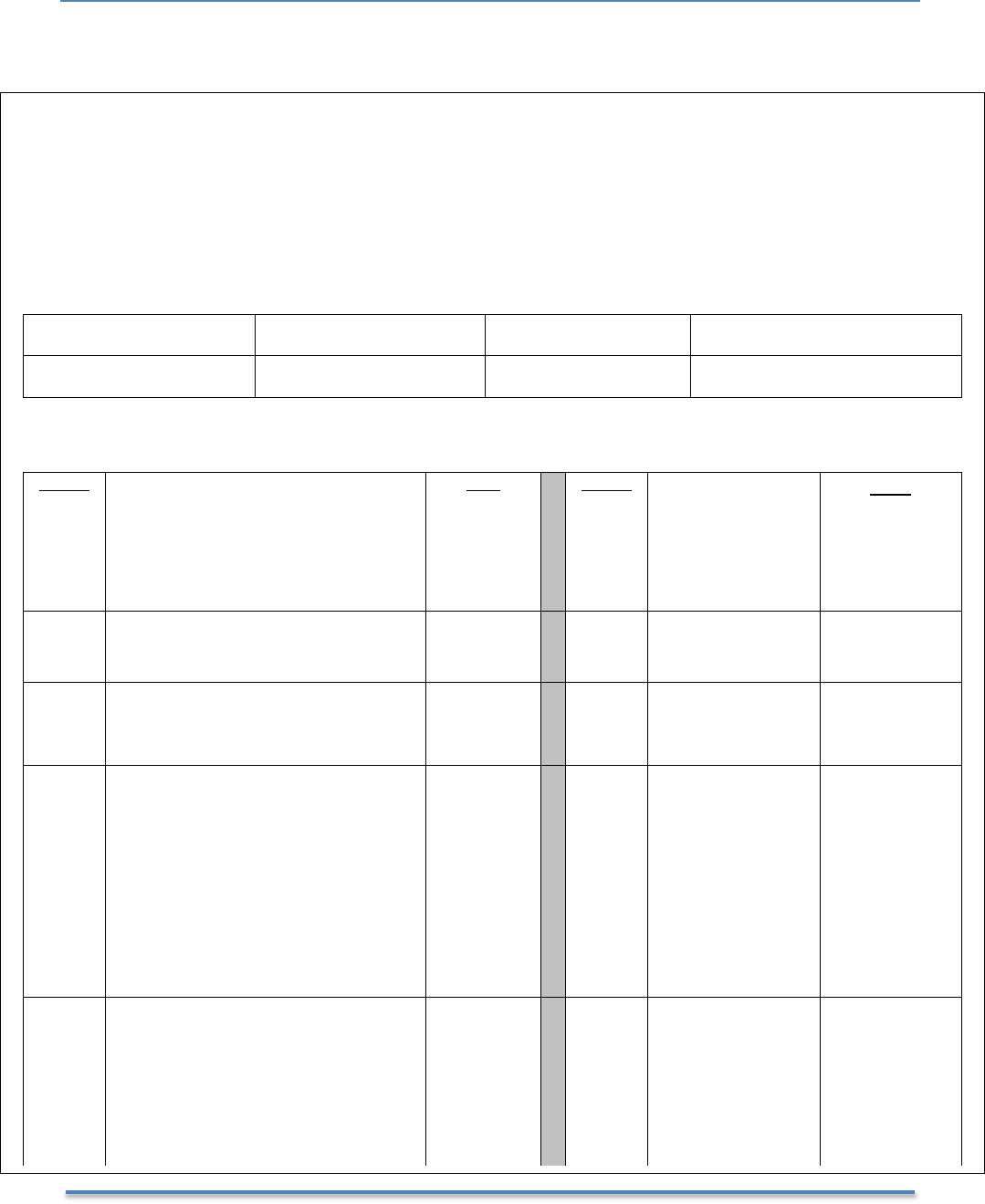

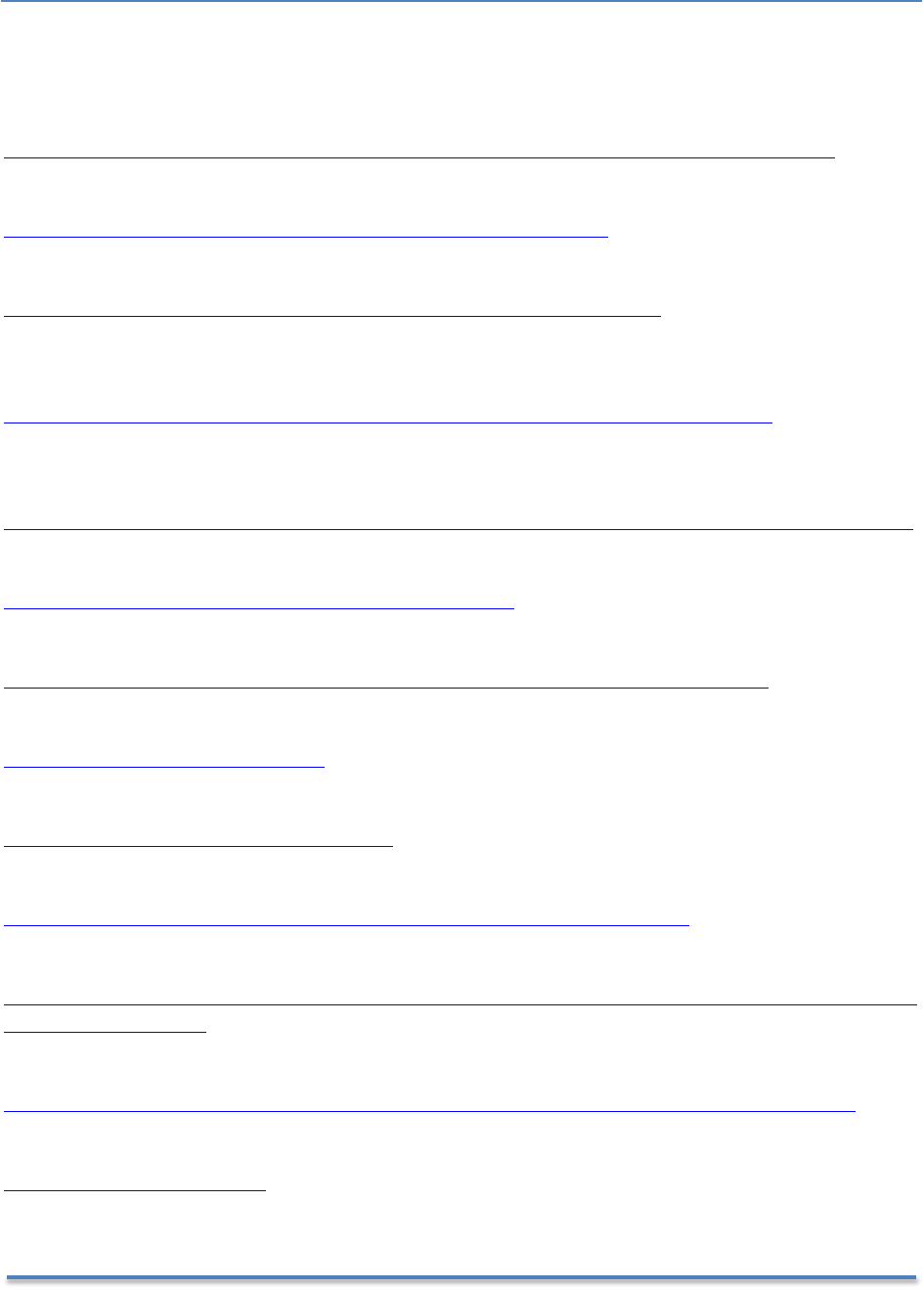

Education-based Evaluation Process for ASD

Below is an example of a process that districts may want to consider as part of the

multidisciplinary evaluation. Districts have found this process to be helpful in determining

whether or not a student meets eligibility criteria as a student with ASD.

Education-based Evaluation

Process for ASD

• Review of Existing Evaluation Data (REED)

• Completion of Evaluation Components

Teacher and Building Staff Interviews

Parent/Family Interview and Home Visit

Observations Across Settings by all

Team Members

Standardized Assessment

Considerations

• Results Review Meeting

• Evaluation Team Report

• Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Review of Existing Evaluation Data

Completion of Evaluation Components

Standardized

Assessment

Considerations

Results Review Meeting

Evaluation Team Report

Individual Education Program (IEP)

Parent/Family

Interview & Visit

Teacher/Building

Staff Interviews

Observations by all

Team Members

The Michigan Autism Council 15 www.michigan.gov/autism

Review of Existing Evaluation Data (REED)

IDEA §300.305 requires multidisciplinary school teams to conduct a REED for all special

education reevaluations. However, a REED is also an option for an initial evaluation,

especially if evaluation data from outside sources are available (e.g. diagnostic reports from

a private clinic, Community Mental Health). The REED can be used to:

• Review available information and assessment data (e.g. clinical diagnostic reports; other

medical reports);

• Determine if the information is sufficient to make a determination of eligibility

(i.e. meets eligibility criteria that impacts academic, behavioral, or social progress in

school that necessitates special education);

• Determine what else is needed to make a determination of eligibility (e.g. observations

to determine impact on educational performance); and

• Establish a plan for gathering the additional information.

For students with a clinical diagnosis of ASD, especially those who are also receiving private

or public insurance benefit services, school teams can expect to receive reports that include,

at minimum, a developmental history and standardized test scores. As such, this

information may not need to be repeated. However, IEP teams are also required to

determine whether the student meets the MARSE eligibility criteria for ASD as well as

determine the impact and necessity for special education services; it is likely that school

observations, teacher interviews, and/or direct assessments may still be needed.

It is important to note that the REED process can be used as a mechanism for increasing

collaboration among clinical and school assessment practitioners. Soliciting additional

information beyond what is provided in reports or inviting clinical staff to participate in the

REED process may enhance such collaboration.

When conducting a reevaluation, it is important to consider that MARSE defines ASD as a

“lifelong developmental disability.” As such, information to determine continued eligibility

should focus primarily on the impact of the ASD on access to and progress in general

education and the continued need for special education, rather than the eligibility criteria

itself. A full evaluation for the presence of ASD is likely necessary only when there is a

potential change in eligibility or the ASD eligibility is questioned.

Completion of Evaluation Components

The ASD Evaluation Component Checklist

A carefully designed evaluation plan supports the coordination of activities of the

multidisciplinary team evaluation. An evaluation checklist can be used to ensure timely

completion of components of the evaluation plan. Teams may want to consider completing

an evaluation component checklist as part of the REED process, and an example is provided

in Appendix C. Should all members of the evaluation team not be present at the REED

meeting, teams may want to consider a separate meeting shortly thereafter to complete the

checklist.

The Michigan Autism Council 16 www.michigan.gov/autism

Teacher and Building Staff Interviews

Education-based evaluations include an interview with the student’s teacher(s) and current

education-based provider(s). Because one of the goals of the education-based evaluation is

to understand how the suspected ASD affects a student in the course of the school day,

including the impact on progress in general education and the need for specially designed

instruction, it is important to obtain information from teachers and others who interact with

the child in the school context (Klin, et al., 2000).

There are a number of options for obtaining building staff input, including utilizing

commercially available checklists, rating scales, or other interview tools. While these may be

useful as part of the evaluation process, they frequently do not align with the MARSE

eligibility criteria and as such should not take the place of direct interviews tailored to the

individual student with a focus on information related to the MARSE eligibility criteria.

Additional options for gathering evaluation information include a facilitated meeting or face-

to-face interviews.

Facilitated Meeting

This option involves scheduling an intake meeting with relevant staff (e.g. teachers,

principal, service providers) facilitated by a member of the evaluation team. A meeting

format allows for rich, efficient discussion among participants about the student’s behavior

in the school context and provides opportunity for participating evaluation team members to

ask specific questions of the staff.

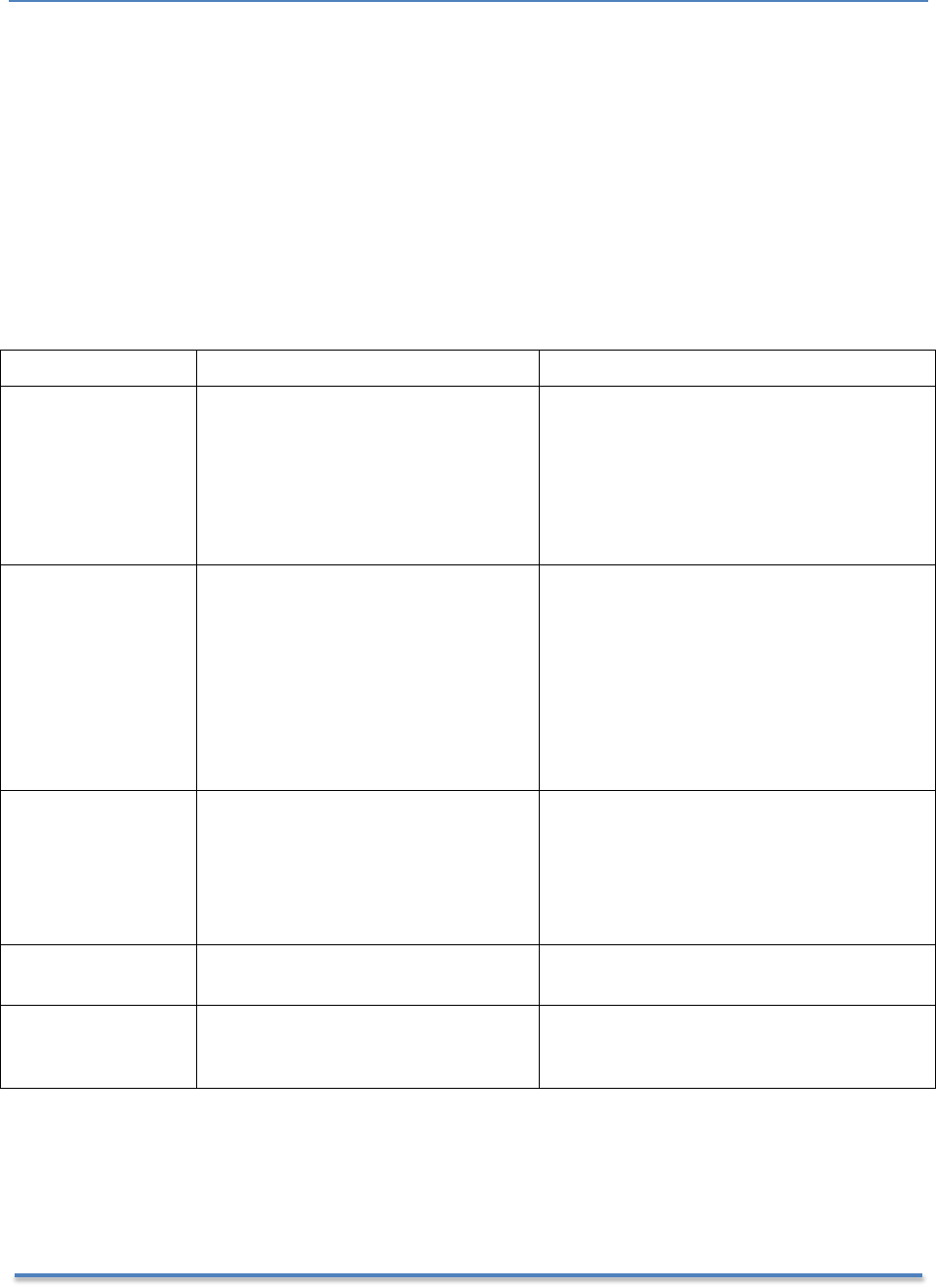

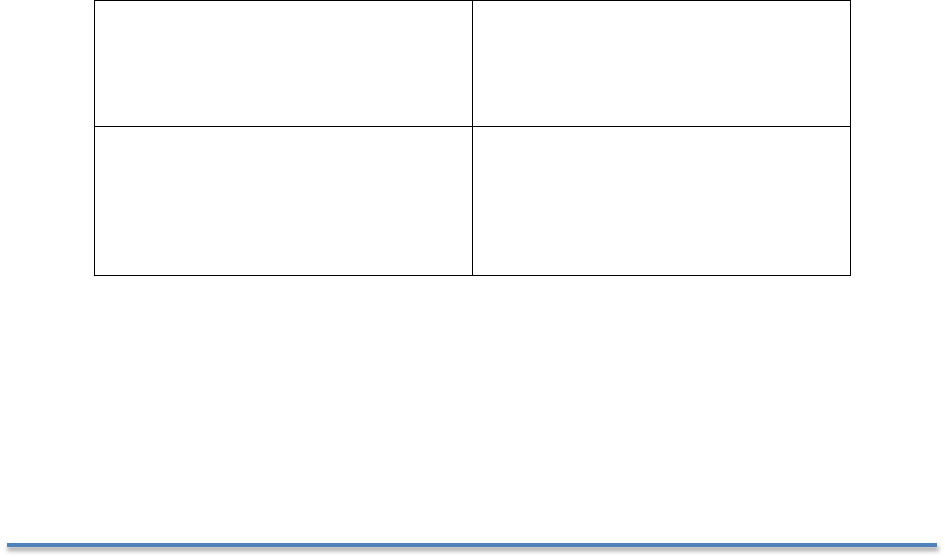

To ensure the discussion stays focused on information needed for eligibility determination,

the facilitator draws a quadrant like the one identified below on a white board or chart

paper, and then initially poses a broad statement, such as “Tell me about <student

name>,” to open the discussion.

Reciprocal Social Interaction

Communication

as it relates to ASD

Restrictive, Repetitive

& Stereotypical Behaviors

OTHER relevant impacting

factors including Sensory,

Cognitive Functioning,

Academic

It is important for the facilitator and other evaluation team members to allow the staff to

initially share any information that they feel is relevant and not limit their input. The

facilitator’s role is to capture all the information provided in the relevant quadrants, plus

anything falling under “other.” As the intake meeting progresses, the evaluation team

members can begin asking follow up questions to elicit more specific information to fill the

quadrants. Because the behaviors displayed by a student with ASD often fall into multiple

The Michigan Autism Council 17 www.michigan.gov/autism

quadrants, the absence of information in any one of the quadrants may be an indication

that the evaluation team should consider alternative areas of special education eligibility.

Face to Face Interviews

Another option for gathering staff information is to have two evaluation team members

conduct individual interviews with relevant staff. Having two members participate allows one

to lead the interview while the second takes notes in a quadrant document (as previously

described) and ask clarifying questions as needed.

The interview can begin much like the facilitated meeting with an open-ended question like

“Tell me about <student name>” or “What does <student name> do that makes you think

he has ASD (or another area of disability)?” The interview can then continue with follow up

and additional questions. Example interview questions and talking points are provided in

Appendix D.

Parent/Family Interview and Home Visit

Education-based evaluations also include an interview with the parent(s) or guardian(s) in

the family home when the student is there. If using this model, at least two team members

would be assigned to conduct the parent interview and home visit. An advantage of a home

visit is that it not only provides another observation setting, but it also helps team members

begin establishing rapport with the family.

Further, seeing reported home behaviors in the environment when they occur can assist the

evaluation team in differential eligibility decisions, as some behaviors attributed to ASD may

be explained by another disability when directly observed. For example, if a parent reports

that a child repeats words over and over, one might attribute this behavior to repetitive

language or echolalia. However, when observed in the home, this behavior could appear

more related to the child wanting something like a cookie and the parent not attending or

responding to the child’s request so he continually repeats the request. Having third party

observers confirm such behaviors can assist in eligibility decisions and also allow the

multidisciplinary evaluation team to better explain these behaviors and perhaps offer

intervention ideas to the family.

During a parent interview a critical question to ask the parents early in the interview is,

“What makes you think your child has ASD?” This may assist the multidisciplinary

evaluation team in sorting out information from the family that may be related to ASD from

other disability areas. For example, parents may indicate that they believe their child has

ASD because he or she has delayed or impaired communication skills. It is important to

highlight this concern within the evaluation process and address it in the evaluation report,

whether or not the student is determined eligible for special education under ASD. Examples

of parent interview questions and developmental history items can be found in Appendix D.

Observations Across Settings by all Team Members

Direct observations in a variety of natural contexts (e.g. classroom, hallway, lunch room,

recess) and across several days provide valuable information. Comprehensive observations

can provide a more accurate picture of how the student communicates, interacts, and

responds to varying stimuli and demands as compared to peers, and consistent behavioral

The Michigan Autism Council 18 www.michigan.gov/autism

patterns across observations increase the validity of the presence or absence of relevant

behaviors.

Observing the student in the school context also provides information about the impact of

the suspected ASD on the student’s progress in the general education curriculum and

settings relative to academic, social, and/or behavioral domains. Multiple observations can

further aid in the determination of the need for specially designed instruction and provide

valuable information for the development of the IEP (e.g. Present Level of Academic

Achievement and Functional Performance (PLAAFP) statement, supplemental aids and

services, goals and objectives).

An important consideration in conducting observations is making opportunities to engage in

activities with the student rather than sitting in the background taking notes. This type of

integrated observation will provide the observer greater opportunities to understand and

consider underlying motivations and immediate contextual variables that may be impacting

the presence of behaviors. This type of investigation is crucial for making differential

eligibility decisions as noted in a subsequent section of this document.

In addition, quantitative data should be collected within the qualitative observation process.

This will highlight the intensity of behaviors and provide further support for the impact and

need for special education. For example, when observing the student’s social interactions,

data can be collected on the frequency of spontaneous initiations with peers and adults as

compared to other students or the number of verbal, visual, or physical prompts needed to

complete classroom routines that peers complete independently. Observation considerations

and data collection templates are available in Appendix E.

Standardized Assessment Considerations

As stated previously, no single assessment method is sufficient for determining special

education eligibility for ASD. The multidisciplinary evaluation team must utilize information

gathered from multiple sources and methods and apply each to the components of the

MARSE criteria. Commercially available standardized assessment tools (e.g. norm-

referenced tests, checklists, and rating scales) may provide relevant information in making

clinical diagnoses of ASD and may actually be required for some diagnoses (e.g. ADOS for

ASD insurance benefit eligibility), but these measures are not based on the MARSE criteria

and thus are not sufficient in making eligibility decisions.

Further, students with ASD often exhibit characteristics (e.g. communication deficits,

difficulty with engagement, challenging behavior, and social reciprocity deficits) that make

assessment challenging and may negate the accuracy of the test results. Below is a list of

common behaviors that interfere with standardized assessment results for students with

ASD:

• Difficulty establishing rapport with the examiner

• Lack of motivation to please the examiner (e.g. deficits in reciprocity)

• Challenges with attention, engagement, and persistence in task demands

• Difficulty transitioning from one activity to another

• Language deficits that make it difficult to understand and follow instructions

The Michigan Autism Council 19 www.michigan.gov/autism

• Stimulus over-selectivity (e.g. attending to irrelevant stimuli)

• Interfering and challenging behaviors

Given these challenges, if the multidisciplinary evaluation team uses standardized

assessment tools, it is critical to report interfering behaviors and identify to what extent the

results of the assessment may not be accurate or reliable. These behaviors can, however,

provide helpful information in understanding the student’s response to stress and

frustration, interpersonal relationships, and communication.

For any standardized measures used in an education-based eligibility determination, the

multidisciplinary evaluation team should provide a rationale for its use. As such,

multidisciplinary evaluation teams should not have a predetermined battery of tools, but

rather determine their use on an individual basis and provide a clear purpose and intent for

using the tool in that particular evaluation (e.g. it answers a specific question that other

assessment methods do not). Teams should also report the technical adequacy of any tool

used including its reliability and validity. Although a complete review of the standards of

technical adequacy of standardized tools is outside the scope of this document, a brief

description is provided in Appendix F.

School teams should also consider the use of standardized tools that may be needed to

make differential eligibility decisions as well as determine the impact of comorbid conditions

on school performance. Caution should be given, however, to the impact of suspected ASD

on resulting scores. For example, school teams may presume that a cognitive score on a

standardized tool is an accurate reflection of ability, and thus consider eligibility under

Cognitive Impairment, when this score is frequently inaccurate for students with ASD due to

the challenges described previously.

To assist evaluation teams in determining if a particular standardized assessment tool

should be utilized, below is a set of questions to consider:

• Does the tool have adequate technical adequacy for making eligibility decisions related

to the suspected disability?

• What is the purpose or intended outcomes of using the tool?

• What questions are you attempting to answer by using the tool, and will the tool provide

that information? Is the information necessary and useful in making the eligibility

decision?

• What are the language requirements of the test, and do they match the ability level and

communication modality of the student?

• Given the student’s behavioral challenges, will the tool likely produce reliable and valid

results?

• How current is the tool (i.e. when was it published and standardized)?

• What are the potential challenges in using the tool (e.g. results are not consistent with

other information)?

Other than using standardized tools as designed, however, evaluators can use these

instruments to gather information about performance under various conditions (e.g. use of

accommodations and visuals supports) or to artificially create conditions that may not be

The Michigan Autism Council 20 www.michigan.gov/autism

easily observed in naturally occurring settings (e.g. responses to someone’s emotional

state).

Such expansions of the use of standardized tools can be beneficial in capturing rich

information on the student’s learning needs, strengths, and challenges. Also called

“breaking standardization,” it is important to remember that such changes to the

administration of the tool invalidate the scores obtained. This can be avoided for some tools

by first administering the test under standardized conditions and then “testing the limits” to

gain additional information. Some options for breaking standardization include the following:

• Administer subscales or items within subscales in a different order so highly preferred

tasks can follow less preferred ones to increase motivation

• Start at the beginning of a particular subscale (easiest item) rather than the age-

suggested starting point to create behavioral momentum

• Take frequent breaks

• Use tangible reinforcers

• Use a multiple-choice or fill-in-the-blank format rather than an open-ended style

• Paraphrase instructions or simplify language to match the child’s language level

• Use terms and phrases that are familiar to the child (e.g., “match” vs. “find me another

one just like this”)

• Use generic verbal prompts (e.g. for a picture vocabulary task, ask: “What is this? This

is a ______.”)

• Use visual supports to aid in the comprehension of instructions

Results Review Meeting

An education-based evaluation may include a summary meeting of the multidisciplinary

evaluation team. Once all of the observations and interviews have been conducted and all

evaluation data collected, the evaluation team may come together to review the

information. The purpose of this optional meeting is to collectively reach a team decision

regarding a recommendation of eligibility, as well as to begin formulating an impact and

need statement that can serve as the basis for the development of the IEP. Although there

may be multiple ways to conduct such a meeting, an example that addresses the challenges

often associated with decision-making is outlined below.

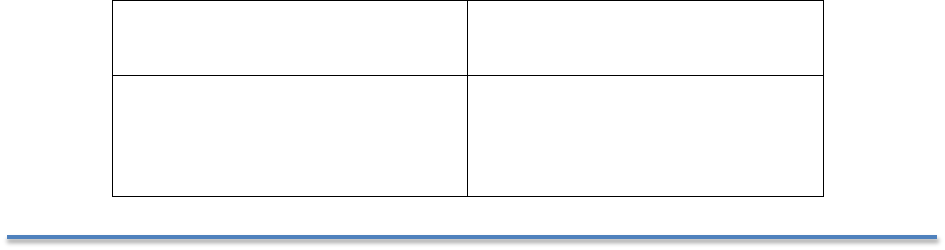

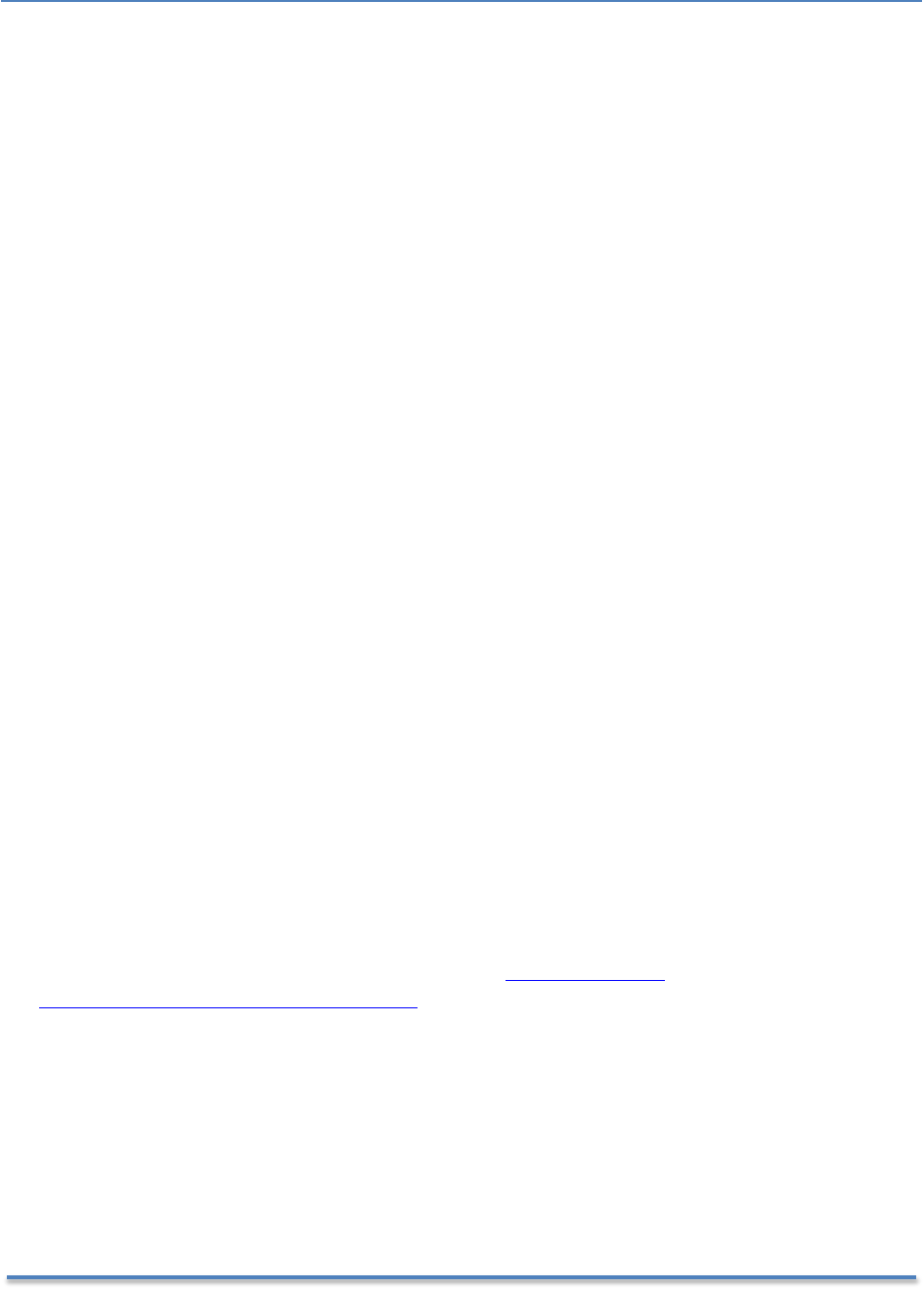

Scheduling a facilitated face to face meeting with the evaluation team (i.e. Results Review

Meeting) allows for a comprehensive and robust discussion from which a recommendation of

eligibility can be most accurately and reliably determined. During such a process, one

member of the evaluation team serves as facilitator and begins by drawing a table on a

white board or chart paper with the following labels:

Reciprocal Social Interaction

Communication

as it Relates to ASD

Restricted and

Repetitive Behaviors

OTHER relevant impacting

factors including Sensory,

Cognitive Functioning,

Academic

The Michigan Autism Council 21 www.michigan.gov/autism

Multidisciplinary evaluation team members then begin to discuss the information obtained

through parent and staff interviews, observations, and any other methods, while the

facilitator lists the information in the appropriate areas in the chart and a note-taker

captures the information in a report template. Some teams have found it helpful to color

code the information based on the source (e.g. parent, teacher, evaluation team) or other

relevant variables. Once all of the information is listed on the board, the team uses the

preponderance of the evidence available to answer the eligibility criteria questions:

Relative to the required number of criteria needed in each broad category:

• Is there a qualitative impairment in social interaction?

• Is there a qualitative impairment in communication?

• Is there the presence of repetitive, restricted, and stereotyped behaviors?

If the answer to any one of these questions is “no,” the student does not meet the MARSE

eligibility criteria for ASD. However, if this is the case, the possibility of eligibility in another

disability category should be considered.

If the answer to each question is “yes,” the MARSE ASD eligibility criteria are met and the

team can go back and identify specific criteria that best represent each category. As a

reminder, in order for the criteria to be met, at least two items must be present in the

reciprocal social interaction area—one in communication, and one in restricted and

repetitive behaviors.

In addition to meeting the MARSE ASD eligibility criteria, the ASD must have an adverse

impact on the student’s academic, social, or behavioral progress and the student must

demonstrate a need for specially designed instruction.

Should impact and need exist, the team can begin to develop a relevant statement that can

serve as the initial foundation for the PLAAFP. To begin this discussion, posing the question,

“What about the student’s ASD is getting in the way of access to and progress in the

general education curriculum and environments?” will assist the team in staying focused on

impact and need versus generating a list of skill deficits.

The last task for the evaluation team to complete during the Results Review Meeting is to

review the evaluation checklist and confirm those team members that will be providing

feedback and recommendations to parents, school staff, and other relevant stakeholders

prior to the IEP, as well as determine which multidisciplinary evaluation team members will

be attending the IEP.

Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team Report

To ensure a clear and concise report that identifies the presence or absence of critical

eligibility characteristics, avoids conflicting information across evaluators, and builds an

accurate case for the conclusions of eligibility, the multidisciplinary evaluation team may

integrate all assessment information into one combined report according to and following

the MARSE criteria.

The Michigan Autism Council 22 www.michigan.gov/autism

The report can explain in detail any and all observation data or other assessment

information that does not align with the conclusions of eligibility. For example, if, during an

interview, the parent reports that the student repeats words constantly (as described in the

Parent/Family Interview and Home Visit section), the report should describe how and why

these behaviors do not support the conclusion of ASD and provide an alternative

explanation for the behavior.

The optional combined report should also include information on the additional two prongs

of eligibility (i.e. impact of the disability on access to and progress in general education and

the need for specially designed instruction). This information will assist the IEP team in

developing a comprehensive PLAAFP and support the development of supplementary aids

and services, goals and objectives, and needed programs and services. An example report

template is provided in Appendix G.

Individualized Education Program

The final step is for the IEP team to determine whether the student meets the ASD eligibility

criteria. Should the student be eligible for special education programs and/or related

services, the IEP team will incorporate the information from the evaluation process to

identify the special education supports and services necessary for the student to receive a

Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE).

Differential Eligibility Decision-Making

To make quality differential eligibility decisions, it is important for multidisciplinary

evaluation teams to understand disorders that mirror ASD and those that are comorbid with

the condition. A number of characteristics associated with ASD (e.g. poor eye contact,

hyperactivity, difficulty with focused attention, difficulty with transitions or changes in

routine, poor peer relationships, repetitive behaviors, delayed language and developmental

skills) are also seen in other developmental or mental health disorders (e.g. Attention

Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Learning Disorders, Cognitive Impairment, Reactive-

Attachment Disorder) (Sikora, 2008).

As such, students with these conditions may qualify under another MARSE eligibility

category (e.g. cognitive impairment (CI), learning disability (LD), emotional impairment

(EI), other health impairment (OHI)). Further, a number of conditions that represent other

eligibility categories are comorbid with ASD, such as CI and EI (specifically regarding

anxiety disorders and depression, in the case of EI). In fact, anxiety disorders and

depression are the primary comorbid conditions in ASD.

As such, it is important for multidisciplinary evaluation teams to review information that

may assist them in differentiating ASD from other disabling conditions. As described in the

Results Review Meeting in Appendix C, teams can use chart paper or a white board to

develop tables or concentric circles that allow them to compare and contrast information

such as:

The Michigan Autism Council 23 www.michigan.gov/autism

Eligibility Criteria

It is critical for evaluation teams to have a solid understanding of the other disabilities and

criteria outlined by MARSE in order to be able to effectively compare and contrast behaviors

and other assessment information within each disability.

Age of Onset of Characteristics and Developmental History

Although some developmental sequences appear similar across disabilities, it is important to

review and discuss the student’s developmental history to assist in differentiating one

disability from another. For example, students on the autism spectrum generally have early

developmental histories that include either the lack of the development of spoken language

not accompanied by attempts to compensate or advanced levels of language, especially in

interest areas. Students with other disabilities may have language deficits, but attempts to

use alternative methods to communicate are present.

Underlying Motivation or Function of Behaviors

Because behaviors can look similar across disabilities, it may help to collect information and

compare and contrast the underlying motivation of behavior, as this may give the

multidisciplinary evaluation team clues into whether one disability or another exists. For

example, refusals to follow expectations and aggression toward others can occur in students

who have ASD and those who are EI. However, in ASD these behaviors are often related to

deficits in social reciprocity or communication skills, and/or a lack of theory of mind,

whereas for students with EI, this may be related to emotional dysregulation, deficits in

self-worth, or a lack of connecting with others as a child (e.g. Reactive Attachment

Disorder).

Additionally, behaviors related to Social Maladjustment, which is an exclusionary factor for

EI, may be seen in students with ASD (e.g. behaviors that violate socially acceptable rules,

not accepting responsibility for actions, or not demonstrating remorse). However, for

students with ASD, these behaviors are related to the deficits described previously as

opposed to behaviors related to conduct disorder or antisocial disorder, which is often the

case for students with Social Maladjustment. For example, the team may need to

distinguish between not caring about social rules and not understanding that social rules

change from situation to situation. They may also need to distinguish between apparent lack

of remorse due to not caring about others’ feelings as opposed to not understanding that

others have different feelings.

History of Interventions

It is important for multidisciplinary evaluation teams to know what interventions are more

likely to be effective for students with one condition versus another. For example, visual

schedules and supports are considered universal supports for students with ASD because

they are an effective way to help the majority of those students increase engagement with

tasks. However, for a student with a conduct disorder, a visual schedule may not always be

as effective.

Once the multidisciplinary evaluation team compares and contrasts relevant variables

associated with the differential eligibility decision, a final recommendation of eligibility must

be made. The most important component of making this final decision, especially for

The Michigan Autism Council 24 www.michigan.gov/autism

students who may meet the criteria in one or more MARSE eligibility areas, is determining

which disability most impacts access to and progress in general education and requires

specially designed instruction. In most cases, if the student meets the eligibility criteria for

ASD but has a common comorbid condition related to ASD (e.g. anxiety, depression) that

could result in another eligibility consideration (e.g. EI), the ASD would typically be

considered the primary disability.

In making this final eligibility decision, it is often helpful for multidisciplinary evaluation

teams to remember that, for some students with complex presentations of their disability,

there will always be instances of behavior that doesn’t fit or align perfectly. As such, the

multidisciplinary evaluation team’s role is to determine, using the preponderance of

evidence, which eligibility is the most representative of the one that is impacting access to

and progress in general education.

Considerations for Evaluation of Young Children

Given the complexities and range of developmental changes in young children, it is critical

for multidisciplinary evaluation team members to have a solid understanding of the range of

typical development in early childhood and the disorders that mirror ASD in this population.

Consideration of development in the areas of communication, cognition, play, emotional and

social functioning, relationships with caregivers and peers, sensory-motor, and self-

regulation should be included in early childhood evaluations. Given that the range of

development can be broad, a higher threshold for determining communication and social

and behavioral impairment may need to be considered.

For example, if a two-year-old child displays a significant communication delay as well as

some difficulty with reciprocal social interactions, the multidisciplinary evaluation team

should consider whether the social difficulties are a result of the significant communication

delays rather than a presentation of a qualitative social impairment related to ASD.

Additionally, this same child may present with motor mannerisms such as hand-flapping

when excited, which for some children is part of the range of typical development. As such,

it would be quite a stretch to consider it representative of repetitive behavior that would

meet ASD criteria. In this scenario, the multidisciplinary evaluation team may determine the

child eligible for having a speech and language impairment (SLI) under R 340.1710 by

considering the social deficits a result of the communication delay and the hand-flapping

within the range of typical development. In this way, SLI is more representative of the

child’s current developmental profile.

Despite these considerations, it is not appropriate to recommend eligibility in another

category to prolong or avoid the ASD eligibility. If, after careful and comprehensive

assessment, the child fully meets the criteria for eligibility under ASD, the multidisciplinary

evaluation team must provide the recommendation of ASD eligibility to the IEP team. The

regular practice of finding a child eligible in the categories of R 340.1710 (“Speech and

language impairment” defined; determination) or R 340.1711 (“Early childhood

developmental delay” defined; determination) to “wait and see” if it is ASD should be

discontinued. According to MARSE, the early childhood developmental delay eligibility

The Michigan Autism Council 25 www.michigan.gov/autism

category should be used only when “primary delays cannot be differentiated through

existing criteria within [other eligibility categories].” In addition, policies that indicate age

cutoffs for finding a student eligible under the ASD classification should also be eliminated.

When considering evaluation for ASD in young children, it is also important for team

members to have a solid understanding of the unique presentation of ASD characteristics.

Although social deficits and delays in spoken language are the most prominent

characteristics evidenced by very young children with ASD (Stone, et al, 1999), there is

often confusion about typical development in the areas of pragmatic language, play, and

social behavior in young children.

Pragmatic Language

Pragmatic language refers to the ability to use new language skills in reciprocal social

interaction with peers. Around the age of four, typically developing children:

• Understand that they need to talk differently to their preschool teacher than to a peer

than to a younger child

• Understand the importance of getting another person’s attention before talking to them

• Use words to request things and communicate their approval and disapproval

• Direct their language to social interactions with adults and peers

• Verbalize out loud their “private speech” about their thoughts, feelings, and hopes as

they play and interact with others

It is important to observe for these behaviors or their absence when conducting early

childhood ASD evaluations.

Play

Observation during play with typical peers is highly recommended when conducting early

childhood evaluations for ASD. The following are guidelines regarding the typical

developmental sequence of play to consider:

• Object exploration—Explores an object, but does not assimilate how to use it in play

(e.g. child makes a stirring motion with a spoon and then drops it)

• As young as 16 months, directs play towards another person (e.g. picking up the

pretend cell phone, making a ringing sound, and handing it to a parent)

• Representational play—Uses “meaningless” objects in a creative way to play a role in

pretend play (e.g. block becomes a cell phone or a train)

• Parallel play—Between the ages of 18 months and three years, plays next to, but not

with, other children; may not appear to interact with but is very aware of the presence

of other children

• Around age three, play moves from objects to imaginary objects or beings (e.g. swing

becomes a spaceship, cup has pretend tea in it)

• Also around age three, begins to animate toys (pretends to feed a doll that is hungry)

• Between ages three and five, integrates more than one act into a sequence or story of

acts; is able to develop play themes with peers and incorporates others’ ideas into play

schemes

The Michigan Autism Council 26 www.michigan.gov/autism

Social

Socially, by age three, the parallel play that is characteristic of the interaction of the two-

year-old is replaced by social play with peers. This can center on shared interests, rough

and tumble play, as well as complicated schemes. By age four, most children prefer playing

with another child to playing alone, with social interactions with peers characterized by

talking, smiling, laughing, and playing. At age four, children begin to display Theory of Mind

and understand that other people may have thoughts, feelings, and ideas that are different

from their own (Leventhal-Belfer and Coe, 2004). As such, consideration of typical social

development must be included in determining social impairment in young children.

The Michigan Autism Council 27 www.michigan.gov/autism

Appendix A

Michigan Administrative Rules for Special Education

(MARSE) Criteria for ASD

R 340.1715 Autism spectrum disorder defined; determination.

(1) Autism spectrum disorder is considered a lifelong developmental disability that adversely

affects a student’s educational performance in 1 or more of the following performance

areas:

(a) Academic.

(b) Behavioral.

(c) Social.

Autism spectrum disorder is typically manifested before 36 months of age. A child who first

manifests the characteristics after age 3 may also meet criteria. Autism spectrum disorder is

characterized by qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interactions, qualitative

impairments in communication, and restricted range of interests/repetitive behavior.

(2) Determination for eligibility shall include all of the following:

(a) Qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interactions including at least 2 of the

following areas:

(i) Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye

gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction.

(ii) Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level.

(iii) Marked impairment in spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or

achievements with other people, for example, by a lack of showing, bringing, or

pointing out objects of interest.

(iv) Marked impairment in the areas of social or emotional reciprocity.

(b) Qualitative impairments in communication including at least 1 of the following:

(i) Delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language not accompanied

by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as

gesture or mime.

(ii) Marked impairment in pragmatics or in the ability to initiate, sustain, or engage

in reciprocal conversation with others.

(iii) Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language.

(iv) Lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play

appropriate to developmental level.

(c) Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors including at least 1 of the following:

(i) Encompassing preoccupation with 1 or more stereotyped and restricted patterns

of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus.

The Michigan Autism Council 28 www.michigan.gov/autism

(ii) Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals.

(iii) Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms, for example, hand or finger

flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements.

(iv) Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects.

(3) Determination may include unusual or inconsistent response to sensory stimuli, in

combination with subdivisions (a), (b), and (c) of sub-rule 2 of this rule.

(4) While autism spectrum disorder may exist concurrently with other diagnoses or areas of

disability, to be eligible under this rule, there shall not be a primary diagnosis of

schizophrenia or emotional impairment.

(5) A determination of impairment shall be based upon a comprehensive evaluation by a

multidisciplinary evaluation team including, at a minimum, a psychologist or psychiatrist, an

authorized provider of speech and language under R 340.1745(d), and a school social

worker.

The Michigan Autism Council 29 www.michigan.gov/autism

Appendix B

Team Considerations and Configurations